Posts Tagged ‘substitutes’

Prof. Adam Martin explains how the drug war has altered incentives for both drug buyers and sellers, leading them to favor higher potency drugs. This is what economists call the potency effect.

Picture a Coke machine next to a Pepsi machine. Let’s say a Coke and Pepsi each cost $1 today. Tomorrow, the price of Coke jumps up to $2. What do you expect will happen? Two things should come to mind. First, fewer people will buy Coke. It’s more expensive. This is the law of demand. The second effect is that some people will now switch from Coke to Pepsi. They are substitutes–when the price of one increases, people buy more of the other. Here are some interesting examples:

Certain nationalities have a relatively harder time gaining American citizenship through immigration and/or naturalization. We’d expect to see an increase in demand for substitutes among these groups. The closest substitute for naturalization is marriage to a U.S. citizen. U.S. immigration policy not only shapes the international marriage market, it does so with national bias.

In times of economic trouble, finding work can be tedious. It requires dedication, persistence, and patience among other things. When job search costs are high, we expect to see an increase in demand for substitutes. The three that come to mind are government assistance, crime, and civil lawsuits.

In times of economic trouble, finding work can be tedious. It requires dedication, persistence, and patience among other things. When job search costs are high, we expect to see an increase in demand for substitutes. The three that come to mind are government assistance, crime, and civil lawsuits.

Huffing is the act of getting high by inhaling toxic fumes. Minor headlines revolve around fears of epidemics among teens. How can we reduce the amount of huffing? Increase the availability of substitutes. Keep some beer in the garage next to the paint. Fewer kids will choose a chemical high when alcohol becomes more available.

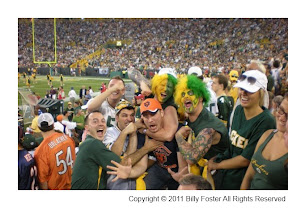

In the spring of 2011, Ray Lewis made the prediction that crime would increase if the NFL lockout prevents the football season from occurring. For some people, like the kids mentioned in his statement, football is a substitute for causing trouble. Ray Lewis (and subsequently LaVar Arrington) left out half the story. A group exists that causes crime because of football. Examples include football drunks and overly aggressive fans (e.g. the baseball incident in May 2011).  Without football, the first group will cause more crime while the second group will commit less crime. Due to the uncertainty of the relative sizes of these two groups, predicting the end result is not so easy. I would’ve suggested that crime would decrease, but I am no better of a predictor as we are all victims of the same type of bias.

Without football, the first group will cause more crime while the second group will commit less crime. Due to the uncertainty of the relative sizes of these two groups, predicting the end result is not so easy. I would’ve suggested that crime would decrease, but I am no better of a predictor as we are all victims of the same type of bias.

Mr. Lewis and Mr. Arrington believe the number of aspiring players is larger than unruly fans. I suggest the opposite. Why? Tversky and Kahneman’s availability heuristic suggests that we tend to think there are more of the types of people or things that can easily be brought to mind. The aforementioned NFL players believe that in the average community there are more aspiring athletes than fans. They grew up in such communities. I grew up in a place with relatively more fans, so I fall for the same type of selection bias by asserting the contrary. None of us has experienced the random sample necessary to make a reliable estimate. One of us is likely right, but based on poor methods of estimation.