Posts Tagged ‘health economics’

Health Economics

Course numbers:

UIC – ECON 215

Loyola – ECON 329

FULL SYLLABI:

UIC | Loyola

“America’s health care system is neither healthy, caring, nor a system.”

– Walter Cronkite

INTRODUCTION

This course will cover supply and demand for health services, the role of insurance in the health care industry, public policy issues, cost and quality regulation. Upon completion of this course you will be able to:

- Use cost-benefit analysis to evaluate health related topics.

- Apply economic principles to the production of health and health capital.

- Use economic tools to analyze health insurance markets.

- Understand the basics of the health care labor market.

REQUIRED TEXTS

The Economics of Health and Health Care, Seventh Edition

Sherman Folland, Allen C. Goodman, Miron Stano

ISBN-13: 978-0132773690

Irrationality in Health Care: What Behavioral Economics Reveals About What We Do and Why

Douglas E. Hough

ISBN-13: 978-0804777971

Prof. Adam Martin explains how the drug war has altered incentives for both drug buyers and sellers, leading them to favor higher potency drugs. This is what economists call the potency effect.

Prof. Angela Dills discusses the economics of drug prohibition.

Hans Rosling’s famous lectures combine enormous quantities of public data with a sport’s commentator’s style to reveal the story of the world’s past, present and future development. Now he explores stats in a way he has never done before – using augmented reality animation.

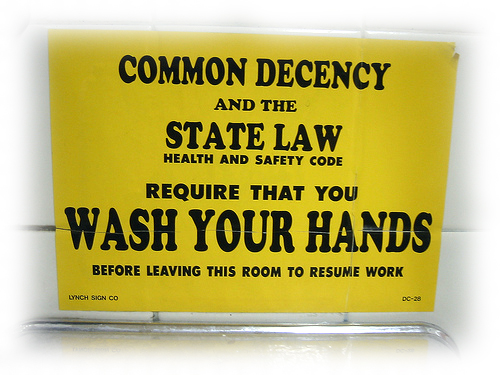

machines purposely cost more to users by requiring more time per sheet. Because of the higher price, the restroom operator knows that fewer towels will be taken per wash. As fewer towels are consumed, less restocking occurs, and eventually the room operates at a lower cost.

machines purposely cost more to users by requiring more time per sheet. Because of the higher price, the restroom operator knows that fewer towels will be taken per wash. As fewer towels are consumed, less restocking occurs, and eventually the room operates at a lower cost.